The collaboration of three European universities in Spain and Italy has resulted in a technique to rapidly manufacture “old” glass to mimic glasses aged naturally for millennia. The same studies also enable to measure viscosity to get a glimpse into the very long-term glass relaxation behaviour.

Researchers from Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain), University of Rome La Sapienza (Italy), and Politecnico Milano (Italy) have devised a technique to rapidly manufacture “old” glass to mimic glasses aged naturally for millennia and measure viscosity to get a glimpse into the very long-term glass relaxation behaviour.

Glass is a rigid material with an amorphous structure. The question is whether it behaves like a really viscous liquid, or whether it ceases completely to flow at low temperatures. Current glass theories predict that glass’s liquid-like molecules stop flowing at a certain low temperature, but from a practical perspective, very high viscosities are nearly impossible to measure.

“We managed to measure relaxation times as large as thousands years, previously inaccessible to experimental determinations, demonstrating the lack of structural arrest at temperature well below the glass transition point or, equivalently, the lack of the viscosity divergence, calling into question our understanding of the glassy state,” says Tullio Scopigno, coordinator of the research and thermodynamics and photonics professor at the University of Rome.

“To this purpose, we had to prepare millenary glasses assembling the molecules one by one, and controlling their age with very high precision. It’s like obtaining perfectly aged wines without having to wait for maturing,” he says. New research shows that glass viscosity does not diverge at a certain low temperature, contrary to current glass theories.

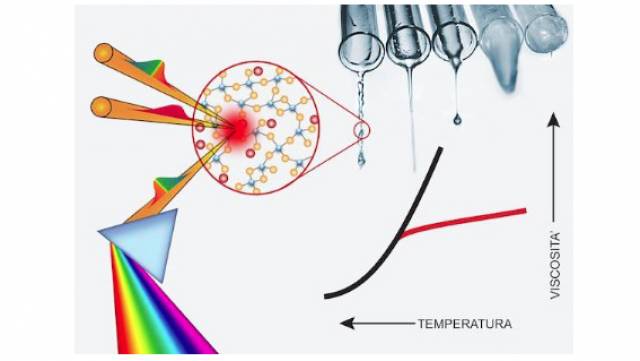

The scientists used physical vapor deposition to form ultrastable glass rapidly. The research team then measured the glass’s viscosity using optical and synchrontron radiation techniques, which allowed them to measure very high viscosity values.

The research suggests that glass viscosity does not diverge at a certain temperature, contrary to what current theories predict. “Scientists have demonstrated experimentally that glass in equilibrium flows visibly at finite temperatures, putting into question one of the pillars of the theory on the vitreous state of glass,” states a Barcelona press release.

The results have practical implications for developing more stable pharmaceutical compounds and more thermally stable organic LEDs (OLEDs) based on the amorphous state, according to the release.

The paper, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is “Probing equilibrium glass flow up to exapoise viscosities” (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1423435112).